In a long-running collaboration with GE Aerospace, researchers at the University of Melbourne in Australia have been steadily working to improve the performance of high-pressure turbine (HPT) engines through computer simulations on leadership-class computing systems. These turbines are the heart of jet engines used in many commercial and military aircraft. Now, with their first project on the world’s most powerful supercomputer for open science — Frontier, located at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory — the team has achieved findings at a level of detail and accuracy never before possible.

With unprecedented simulations of 10 to 20 billion grid points in size with 1017 degrees of freedom (variables that must be solved), the Melbourne team investigated how the surface degradation of turbine blades affects their aerothermal performance. Such component wear may be an expected mechanical outcome, but making accurate predictions of its effects on the engine requires computer models with a level of complexity that was not feasible until now.

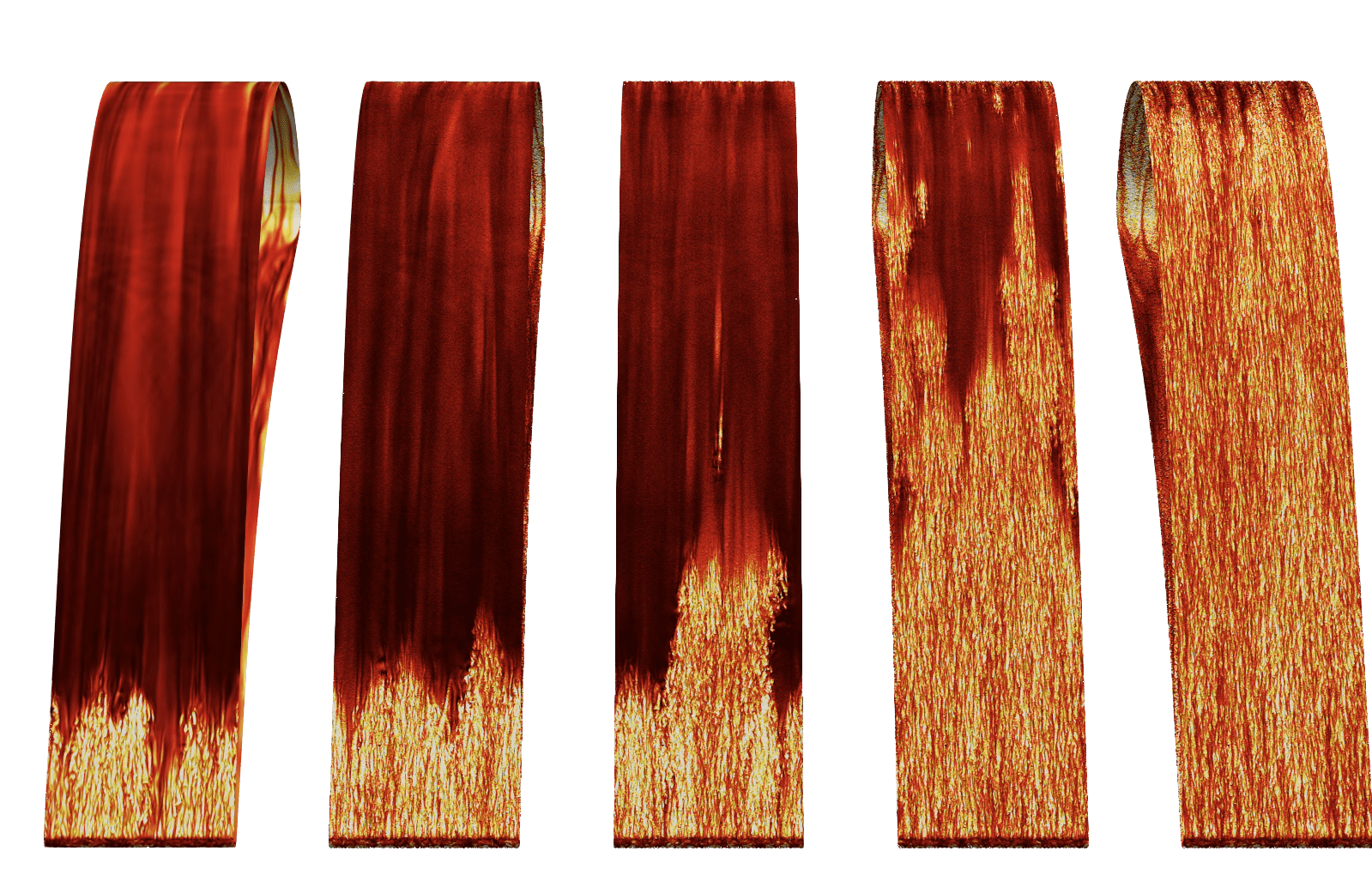

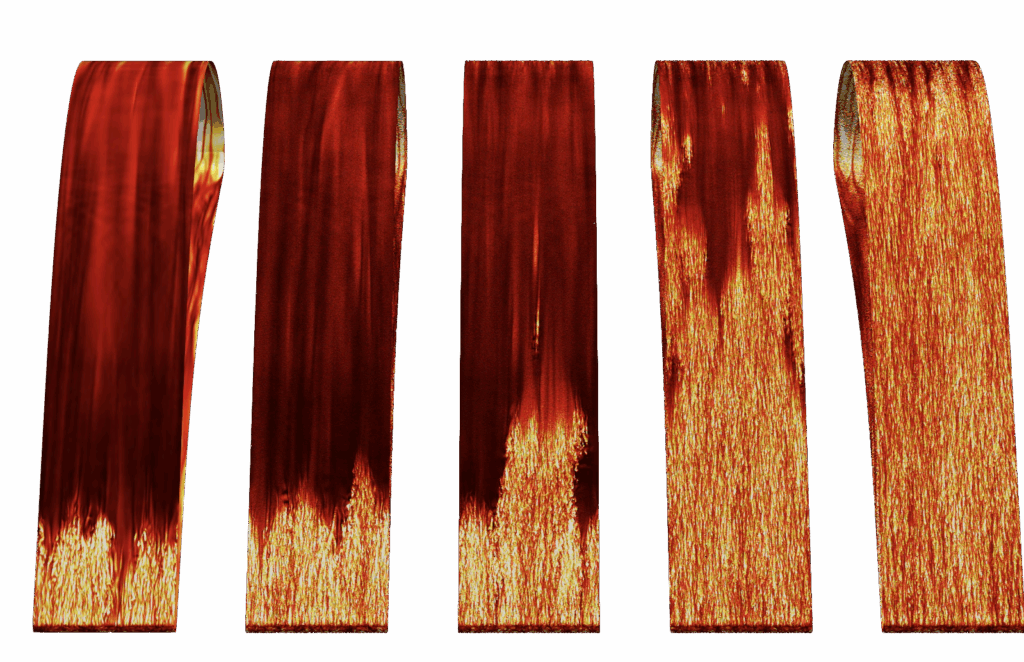

This visualization shows the instantaneous wall heat flux on the suction surface of turbine blades in a high-pressure turbine engine. The levels of surface roughness in the leading-edge region are increasing from left to right, and affects how the engine transfers heat along its turbine blades. Credit: Thomas Jelly, University of Melbourne, Australia

Frontier supercomputer powers record-breaking jet turbine simulations

“Degradation happens at the microscale, and that makes it very difficult to simulate because of the discrepancy in time and length scales — you’ve got a big blade, but then you’ve got all these minute changes to the surface,” said Richard Sandberg, chair of Computational Mechanics in the University of Melbourne’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. “To capture their effects on the global picture requires very, very large simulations. Our cases are an order of magnitude larger than previous ones, and that’s exactly why we need Frontier to do this. The reason why nobody has looked at surface degradation with this level of fidelity is because it just wasn’t possible before we had machines like Frontier.”

The results could help improve jet engine efficiency and durability, reducing fuel use and extending component life — advances that support national goals for energy efficiency and technological competitiveness.

GE Aerospace has been working with Sandberg and his team for more than a decade to better understand HPT fluid dynamics, which are extremely complex because of the highly turbulent flow, the film-cooling air used to protect the turbine airfoils and the interior gas temperatures that can exceed 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit (2,000 degrees Celsius). Using the exascale power of Frontier, Sandberg’s team can now produce high-resolution simulations that can untangle those forces and accurately predict how blade surface degradation affects HPT performance in, for example, jet engines.

“The surface roughness of turbine airfoils increases over time due to in-service degradation. This roughness can significantly increase aerodynamic loss, which leads to worse fuel efficiency, and heat flux, which leads to reduced durability and more frequent engine maintenance,” said Greg Sluyter, a senior engineer on the Turbine Aerodynamics team at GE Aerospace. “Dr. Sandberg and his team’s work is providing a step-change improvement in our understanding of these roughness effects and how factors such as the distribution of roughness levels affect the severity of these impacts. An end goal of this work is to design turbine airfoils that are more tolerant to surface roughness degradation.”

The project’s findings, published in the ASME Journal of Turbomachinery, are from the first in a series of efforts by Sandberg’s team and GE Aerospace researchers to enhance HPT performance by leveraging Frontier. The team’s initial results reveal that the field’s previous notions of how roughness affects viscous flow in simple geometries (such as the flow through a circular tube) don’t apply well to the complex geometries of turbine engines.

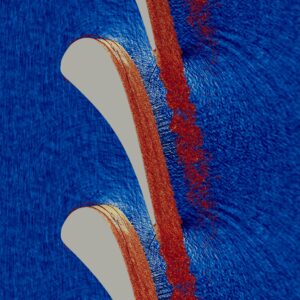

Flow past HPT vane with micron-scale surface roughness at Reynolds number = 590,000 and Mach number = 0.92. Data include instantaneous density gradient (blue) and instantaneous vortical structures (red iso-volumes). Credit: Thomas Jelly, University of Melbourne in Australia

“All of our understanding of roughness effects has been built on what we call canonical problems. But when you look at roughness effects on a blade, it’s actually quite different because there are a lot of fluid dynamic and thermodynamic phenomena that are absent in these canonical cases but present inside jet engines,” said Thomas Jelly, the lead University of Melbourne researcher on the project and first author of the paper. “I think that one of the key aspects of this paper is that it really challenges the contemporary understanding of roughness effects in a much more realistic and complicated environment. Our data shows that the de facto standard modeling approaches that have been built up over the years are not applicable to these more complicated, industrially relevant flows.”

Turbine blades require more complex computer models because their surfaces transition between two states of flow: laminar, in which fluid moves smoothly, and turbulent, in which fluid movement is chaotic or irregular. Surface roughness plays a crucial role in determining where the transition from laminar to turbulent flow occurs, which is key to understanding how heat moves around in the engine and an insight that can inform new turbine designs.

For example, one way of increasing a turbine’s thermodynamic efficiency is by increasing the temperature inside the engine. However, that temperature may exceed the melting point of some engine components, which means very complex cooling technologies must be used to protect the blades. Yet, adding more coolant may also reduce the overall output of the engine.

“The materials that make up the blades have a certain heat capacity, so you need to have clever designs to keep those blades cool but at the same time extract enough energy so that you’re not wasting the fuel that you burn. So, to do that, there are a lot of physics that you need to understand, and they’re not easy to collect from a running engine,” said Kalyan Gottiparthi, a computational scientist in ORNL’s Advanced Computing for Life Sciences and Engineering Group and the scientific liaison for the project. “But what Dr. Sandberg’s group has developed is a unique computational code that can do what we call a direct numerical simulation, which doesn’t add any assumptions in the turbulence modeling and can actually resolve the blade surface at the microscale.”

To design and run computer simulations with maximum fidelity, the Melbourne team updated Sandberg’s High-Performance Solver for Turbulence and Aeroacoustics Research (HiPSTAR) to be the first truly engine-representative, 3D, high-fidelity model of an HPT with microscale surface degradations. Optimized for Frontier’s AMD GPU accelerators, HiPSTAR’s simulations of surface degradation took a few weeks to compute. For comparison, they would have required more than 1,000 years to complete on a laptop computer.

“These engine-representative models are providing insights into the aerodynamic behavior of HPTs under real-world operating conditions, enabling us to obtain information about the HPT aerodynamic and thermal performance at engine conditions with far more detail than we can measure experimentally,” Sluyter said.

This animation shows suction-surface transition mechanisms on a high-pressure turbine vane with micro-scale surface roughness, including instantaneous pressure (left), wall-heat flux (middle) and viscous drag (right). Credit: Thomas Jelly, University of Melbourne in Australia

Insights from Frontier advance fuel efficiency and engine design

The GE Aerospace team is using these insights in the design of its next-generation HPTs, including GE Aerospace’s work with NASA on their Hybrid Thermally Efficient Core Project to develop more fuel-efficient commercial aircraft engines.

The surface degradation of turbine blades and its effect on heat transfer is one piece in the complicated puzzle of engine performance enhancement that Sandberg’s team is putting together on Frontier. With a three-year allocation of Frontier compute time from DOE’s Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment (INCITE) program, the collaborators are continuing their investigations to improve engine efficiency.

Now that the team has a better understanding of how an engine’s heat transfer flows along its turbine blades, as well as the role that degraded blade surfaces play in that process, they are looking at how best to cool those areas.

“Our current project is designed to look into the very details of how a cooling film interacts with the degraded surfaces. We want to ultimately understand how that surface degradation affects that coolant,” Sandberg said. “In the long term, we will develop models that can better predict this so that the designers can have more confidence in their predictions and therefore design a more efficient engine.”

Access to high-performance computing systems such as (the now decommissioned) Summit and Frontier at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility — a DOE Office of Science user facility at ORNL — has enabled researchers to perform the detailed simulations needed for this work.

“Access to leadership computing has been essential to this work and has significantly supported GE’s research goals. These simulations run by Dr. Sandberg’s team have used over 2,500 Frontier nodes, requiring leadership-class supercomputing to run in a reasonable amount of time,” said Paul Vitt, chief consulting engineer for the Turbine Aerodynamics team at GE Aerospace. “Through DOE’s INCITE program and our collaboration with ORNL, we have been able to accelerate our progress in using advanced simulation techniques to innovate faster.”

Related Publication

Thomas O. Jelly, Massimiliano Nardini, Richard D. Sandberg, Paul Vitt, and Greg Sluyter, “Effects of Localized Non-Gaussian Roughness on High-Pressure Turbine Aerothermal Performance: Convective Heat Transfer, Skin Friction, and the Reynolds’ Analogy,” ASME Journal of Turbomachinery (May 2025): DOI: 10.1115/1.4067354.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for DOE’s Office of Science, the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States. DOE’s Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.