Researchers use Jaguar to shed light on the last major dark spot in astrophysics—turbulence.

The sight of an aurora evokes feelings of mystery and awe in the weekend star gazer and scientist alike. The stargazer may ponder the vastness of our

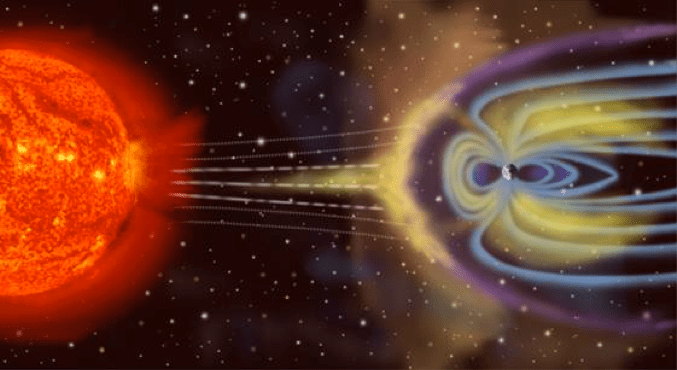

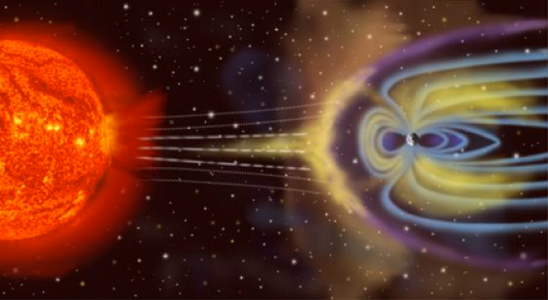

The solar wind, originating in the million-degree-Celsius solar corona, blows through the solar system and interacts with the protective magnetosphere of the Earth. Huge blobs of plasma, known as coronal mass ejections, occasionally erupt from the solar surface and can interfere with satellite communications when they collide with the Earth’s magnetosphere. Image courtesy of NASA.

universe or how such vivid color can be created in space, but for the scientist, the questions lie in the composition of the aurora—and how little we actually know about it.

The ionized gasses known as astrophysical plasma give us auroras, comet tails, solar wind, and much of the spiraling matter falling into a black hole. Created when a gas becomes so hot that electrons are pulled away from atoms, such plasma is a fourth state of matter, in addition to solids, liquids, and gasses, and makes up much of the known matter in space. Scientists began investigating the mysteries of space plasma decades ago but are still at a loss to explain many aspects of plasma’s behavior, especially the random, chaotic movements known as turbulence.

“Turbulence has always been a major unsolved problem in physics, and in the realm of space physics it’s a particularly important one,” said University of Iowa astrophysicist Gregory Howes. A team led by Howes is pursuing this mystery on Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s (ORNL’s) Jaguar supercomputer. The team was allotted time through the Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment (INCITE) program.

The project initially used the GS2 code, which computes the behavior of ions and electrons in a doughnut-shaped tokamak fusion reactor. To make the application more useful for space plasmas, Howes’s team stripped the code of its tokamak geometry, creating a faster simulation code with shorter development time. The resulting code—called AstroGK—was completed in 2007 and is routinely run using 51,000 of Jaguar’s 224,000 processing cores.

Without comprehending the effect of turbulence, scientists cannot understand the unusual properties of plasma, from its role in heating up the supermassive black hole in the center of our galaxy to the creation of the solar wind that blows away from the sun, creating a giant bubble surrounding the solar system.

Although some characteristics of the solar wind are well understood, many others are still a mystery, such as the way it is heated by turbulence. “Plasmas are notoriously complicated entities,” said Howes. “The range of phenomena is amazing.”

Laws of attraction

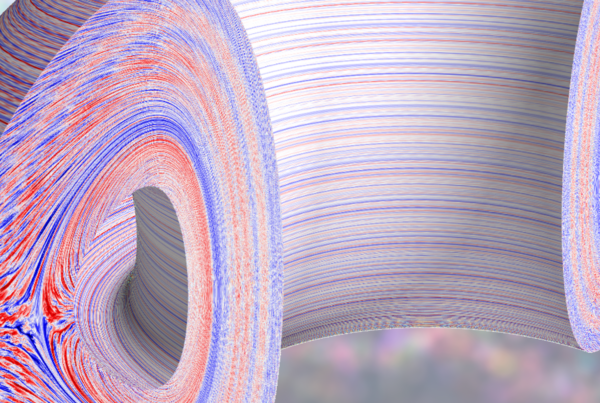

The turbulence of space plasmas is fundamentally unlike the more familiar turbulence of wind and water. On Earth the particles in air and water constantly collide with one another and therefore move at essentially the same speed. This uniformity allows them to be described as a fluid, depending on only density, velocity, and temperature.

Astrophysical plasmas do not behave this way. The particles in them rarely collide and can therefore travel at different speeds. In addition, not only do these particles move along with the plasma as a whole, but they also bounce around erratically within the plasma, adding another three-dimensional behavior that must be accounted for. This combination of characteristics requires a kinetic, rather than a fluid, description of the plasma.

“Essentially the physics of the plasmas is six dimensional, and a seventh [dimension] is time. This is very computationally challenging, and this leads into why we need to use the resources through INCITE,”Howes said.

Turbulence in astrophysical plasmas can have different causes depending on where the plasma is and how a magnetic field is influencing it. In the atmosphere above the sun’s surface, the solar corona, turbulence plays an unknown role in heating the plasma from 6,000 to about 1 million degrees Celsius (roughly 10,000 to 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit). Intense heat and gravitational pull from the sun create turbulence in solar wind. On the other hand, the gravitational pull from a black hole creates turbulence by forcing the arms of gaseous matter—known as accretion disks—to slide against one another as they move toward the center.

Howes’s team focuses on understanding the heating of the solar wind plasma as the turbulence is dissipated at scales from kilometers to hundreds of kilometers. Petascale supercomputers such as Jaguar, which is capable of more than 2 quadrillion calculations per second (2 petaflops), have finally allowed scientists to simulate the intricate web of motions within space plasmas and unravel the physical mechanisms involved in the turbulence and plasma heating.

Even with petascale systems, however, getting meaningful data out of six-dimensional simulations is difficult. Much past research in the field has relied on magnetohydrodynamics, which treats the plasma as a fluid and calculates results based on the three spatial dimensions. This approach is limited in that modeling the heating of the plasma requires a kinetic, rather than a fluid, description.

To more accurately describe the kinetic properties of solar wind, the team uses a mathematical approach called gyrokinetic theory, which eliminates unnecessary physics from kinetic theory to more efficiently simulate solar wind turbulence. This approximation averages over the spiral motion of ions and electrons in the interplanetary magnetic field, reducing the kinetic descriptions to five instead of six dimensions. Some of the solar wind physics may lie outside the gyrokinetic description, though. “It is an approximation, and one must keep that in mind doing this research,” Howes explained.

Travelling outward

This team has secured time on Jaguar for 3 years. In 2010 it focused on establishing the connection between turbulence in the solar wind, the resulting generation of heat, and the eventual fate of that heat. Knowing how the turbulence behaves would contribute to our ability to predict coronal mass ejections—massive bursts of solar wind ejected from the sun that are capable of disrupting satellites and GPS location systems. Allowing scientists to anticipate “space weather” would allow for less disruption of communication systems on Earth.

Research into space exploration has long been concerned with the effect of high-energy particles on the human body. Finding the origins of these particles and being able to calculate their acceleration and movements would also allow us to better predict how such particles travel through the solar system. Such insight could give astronomers on the ground time to warn astronauts fixing a space station or satellite that potentially fatal particles are heading toward them and that they should move to somewhere safe.

For Howes’s team, though, these questions will come later. Its current, fundamental aim is to understand a material that, despite its abundance in space, is still as mysterious to us as the dark side of the moon.

This research may not be able to paint the whole picture of plasmas yet, but it is already giving researchers the basic information to explain some of the happenings in our vast and mysterious solar system. — by Eric Gedenk