Researchers from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland (ETH Zurich) have developed a new framework to capture the quantum mechanical effects inherent in the designs of nanoscale electronic devices, such as next-generation transistors. The framework can provide semiconductor engineers with much more accurate insights through advanced modeling capabilities unavailable in current state-of-the-art simulation tools.

The team’s open-source code, Quantum Transport Simulations at the Exascale and Beyond (QuaTrEx), also demonstrated a record-breaking level of performance on the exascale-class Frontier supercomputer at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory. QuaTrEx produced transistor simulations roughly an order of magnitude larger than previous quantum transport simulations of interacting electrons in materials. Using 37,600 AMD GPUs, QuaTrEx sustained full-precision (64-bit) performance while simulating a system of 42,240 atoms at 1.15 exaflops — very close to Frontier’s June 2025 High Performance Linpack score of 1.353 exaflops.

These computational achievements have made the ETH Zurich team finalists for the Association for Computing Machinery’s 2025 Gordon Bell Prize for outstanding achievement in high-performance computing (HPC).

“We are extremely happy. It is a very high recognition, probably the highest that you can expect in the world of HPC,” said principal investigator Mathieu Luisier, a professor in the Department of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering at ETH Zurich. “It says a lot about the work that has been done, and on top of that, it gives visibility to the code. Our ultimate goal is that others will use QuaTrEx — in particular, industrial partners.”

Understanding next-generation transistors

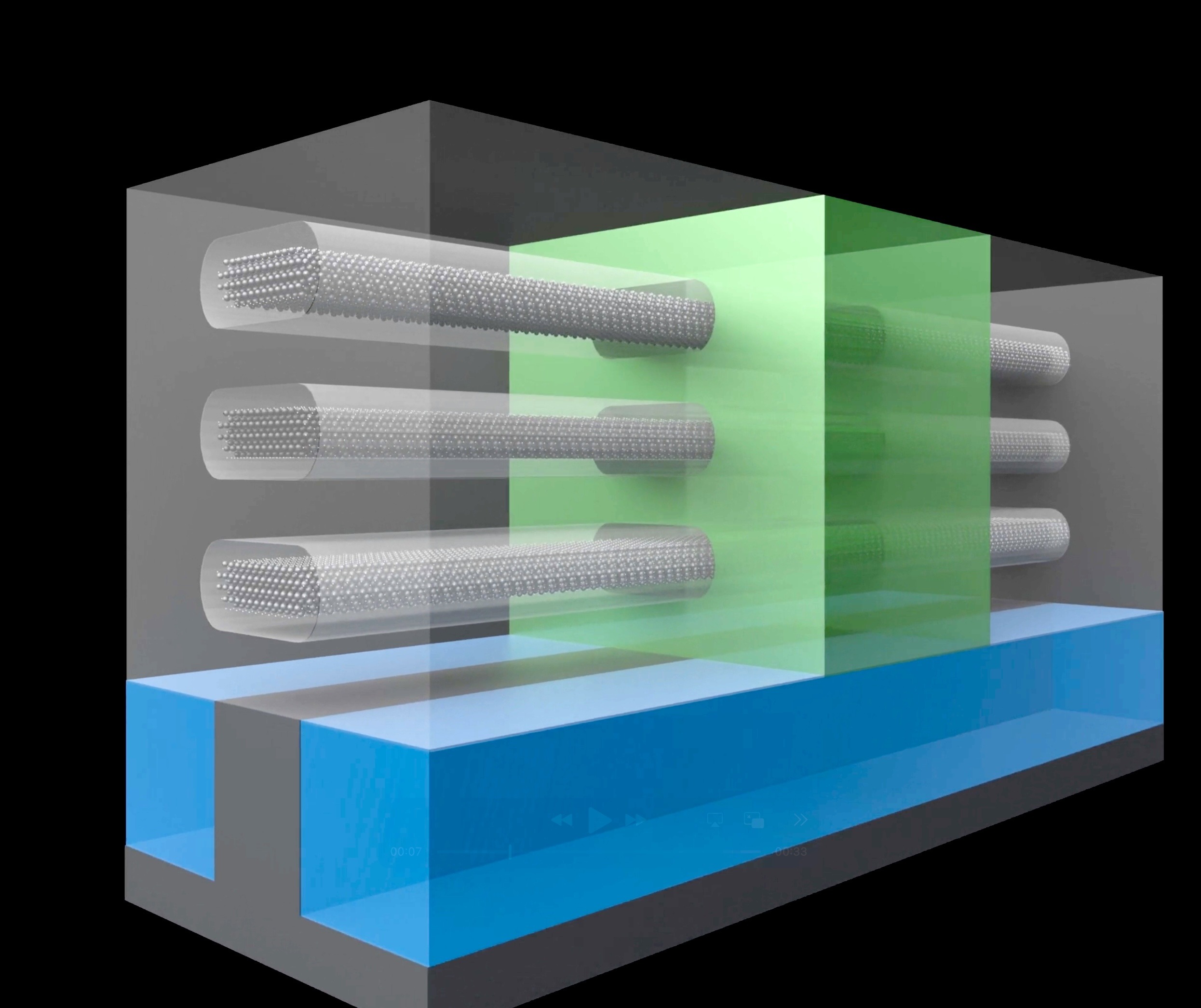

QuaTrEx is especially suited for tackling the design challenges of nanoscale transistor architectures. Even though Moore’s Law — the idea that the number of transistors on a chip doubles every two years — may no longer be strictly true, chipmakers are still seeking performance gains through innovative solutions. For example, nanoribbon field-effect transistors (NRFETs) are emerging as the latest, silicon-based technology that can operate at ultrascaled dimensions while providing the necessary computing power for modern electronic devices, from cell phones to GPUs.

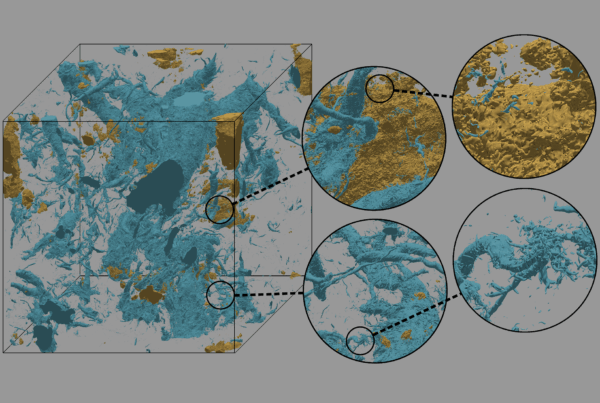

However, NRFETs have a potential drawback associated with their design: they’re so small that new issues arise. The stacked nanoribbons used to control the flow of electrons are potentially less than 5 nanometers — about 1/20,000th the width of a human hair — at the currently manufactured 2-nanometer technology node. When the nanoribbons are that thin, the electrons can interfere with one another.

“The cross section of these transistors is so small, and you have such a high population of electrons located in that region, that they start to strongly interact with each other. It is more or less the same effect you learned as a child — if you put two negative charges together, they tend to repel each other,” said Luisier, whose research group also won the Gordon Bell Prize in 2019. “If you now have hundreds of negatively charged electrons in a volume as small as 1,000 cubic nanometers, a lot of interactions are created that might critically affect the functionality of transistors. These electron-electron interactions must be accounted for in design models.”

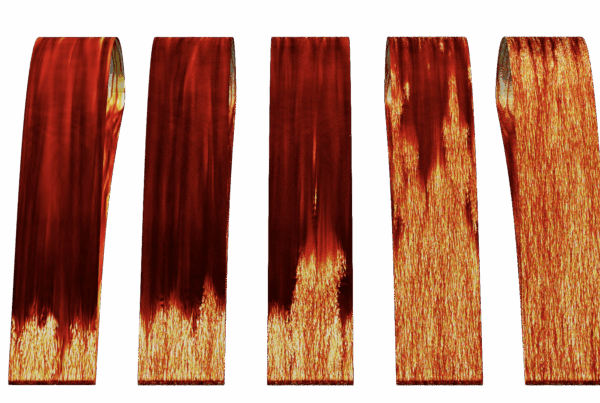

The ETH Zurich team used QuaTrEx on Frontier to simulate interactions in NRFETs made of 42,240 atoms. It was the first device simulation based on a physics framework that accounts for such quantum (atomic level) effects in realistic structures, and this work can enable semiconductor engineers to make more reliable design predictions for nanoscale electronic components such as NRFETs.

“The semiconductor industry mostly still relies on classical physics, which means Newton’s laws of motion, to design even the most advanced transistors. To capture missing quantum effects, classical device simulators provide a lot of ‘knobs’ that can be freely turned, thus allowing engineers to reproduce almost any experimental measurement coming out of a semiconductor fab,” Luisier said.

“The problem with that approach is that your prediction capabilities are limited. If you change the geometry or material of an existing transistor design to test something new, you cannot fully trust the trends obtained,” Luisier continued. “Our simulator addresses this issue in the sense that it implements more fundamental physical principles and is therefore expected to naturally capture effects occurring at nanoscale dimensions. Such improvements come, however, at the expense of much higher computational cost that only leading computing facilities can currently support.”

Nanoribbon field-effect transistors are emerging as the latest, silicon-based technology that can operate at ultrascaled dimensions while providing the necessary computing power for modern electronic devices, from cell phones to GPUs. Credit: Nicolas Vertsch and Alexander Maeder from ETH Zurich.

Achieving advanced computing in an unexpected language

Given QuaTrEx’s ability to achieve more than an exaflop of full-precision performance on Frontier, it may surprise some computational scientists that the code is written in the general-purpose Python programming language, which allowed the team to leverage precompiled, highly optimized libraries in a portable way.

“Many people may think that scripting languages are not ideally suited to get good performance, but we showed that this is not really the case. Python’s programming environment fully supports HPC applications,” said Alexandros N. Ziogas, the leader of QuaTrEx’s development and a research scientist at ETH Zurich.

Python’s flexibility also allows the code to run on different computing platforms, including the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre’s Alps supercomputer and its NVIDIA GPUs.

“One of our goals was to have QuaTrEx be as portable as possible to be usable at different scales and on a range of hardware. You can run a simulation on your workstation — but, of course, with only very few atoms — and then the same codebase runs at the full scale of Frontier,” said Nicolas Vetsch, a doctoral student at D-ITET of ETH Zurich.

Luisier and his team of 10 researchers continue to develop the code to include more electron interactions, such as those with lattice vibrations, which cause atoms to vibrate and thereby heat up your cell phone, for example. They view their recognition as Gordon Bell Prize finalists as a testament to the entire team’s contributions to QuaTrEx.

“It is nice to have that validated — that we took care to develop the code with collaboration in mind. This was a group effort. It could not have been written by two people,” Vetsch said. “All team members contributed key parts to the code, which was made possible by the modular design approach we took when writing this Python code. Choosing Python also enabled our development speed — the first commits to this codebase were made barely one year ago, and we already have sophisticated transistor simulations running at the exascale.”

Torsten Hoefler, professor at ETH Zurich and a member of the team, added, “This work combines record-breaking achievements in terms of sustained exascale performance and scalability with the largest, high-fidelity simulations of nanotransistors. We believe these results will significantly benefit the design of future processors.”

In addition to Luisier, Ziogas, Vetsch, and Hoefler, the QuaTrEx team includes Alexander Maeder, Vincent Maillou, Anders Winka, Jiang Cao, Grzegorz Kwasniewski, and Leonard Deuschle, all of ETH Zurich.

The winners of the Gordon Bell Prize will be announced at this year’s International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage, and Analysis (SC25), held in St. Louis, Missouri, from Nov. 16 to 21.

Frontier, the world’s most powerful supercomputer for open science, is managed by the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, a DOE Office of Science user facility at ORNL.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for DOE’s Office of Science, the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States. DOE’s Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.